Can Luxury Products Have Soul? Exploring The Materials Of Charles Simon

It’s the soul that the craftspeople embed with their hands, their minds and their hearts.

There’s an old episode of the Simpsons where Bart sells his soul to Milhouse for $5. It’s a classic.

After the transaction, Bart writes ‘my soul’ on a piece of paper and hands it over; hilarity ensues. Bart realises that his soul is in fact real, and he’s lost it. How does he know this? Well, as he walks up to the automatic doors of the Quicky-Mart, they don’t work. Then he tries to fog up the ice-cream cabinet with his breath and, you guessed it, that doesn’t work either.

Questionable metaphysics aside, it’s an interesting way to turn what is a rather unclear concept into something tangible. A Bart-shaped face print on the door and a fog-free fridge tell us all we need to know about the presence of a soul.

It got me thinking, what is a soul, and is it just humans that have them? What is that special sauce that makes us more than the sum of our parts? It’s a tough question, and one that I’ll leave to the real writers for now, but perhaps there’s something to it that we could explore within the context of watchmaking and luxury. What makes a product special is not just how it’s made, who made it or what it’s made from. Or is there something else going on, something much more magical?

For anyone wondering, Bart ends up getting his soul back by eating the piece of paper on which he wrote ‘MY SOUL’. Makes total sense.

What Makes a Brand Special? From The Simpsons to The Apple Store

The Apple Store is a fascinating place. It’s so calm, organised and helpful. I read a book about it once, and the way it’s run is fascinating. Among many others, they have this rule that every customer must be acknowledged within 10 seconds or less, wild for a small retail space let alone a huge one like Apple. They also do this strange thing at the end of every shift.

Along with cleaning grubby fingerprints and taking off whatever primary coloured shirt they wore that day, the staff will adjust the screens of the laptops and iMacs so they are just out of view of the customer. Have a look next time you go for your early morning Apple store visit; every screen is adjusted vertically. At first, this didn’t make any sense. Why make it more difficult for the customer? But after reading the book, I understood. Apple will do anything to make you touch and interact with their products because they want you to feel the magic. Humans crave tactility and primarily judge the value of something based on the way it feels.

Apple knows that its products are incredibly well-engineered and they want to use that as a selling point. No better way to force this than making you touch the product. This is something at which the watch industry does a shocking job. The watches are behind glass, and even if you do get to try them on, they’re covered in plastic. It’s necessary I suppose, but a real shame.

I tell you this to set the scene for exploring a brand I love, the Canadian hand made accessories atelier Charles Simon, and how it makes accessories that are more than the sum of their parts.

Let’s explore the materials of Charles Simon.

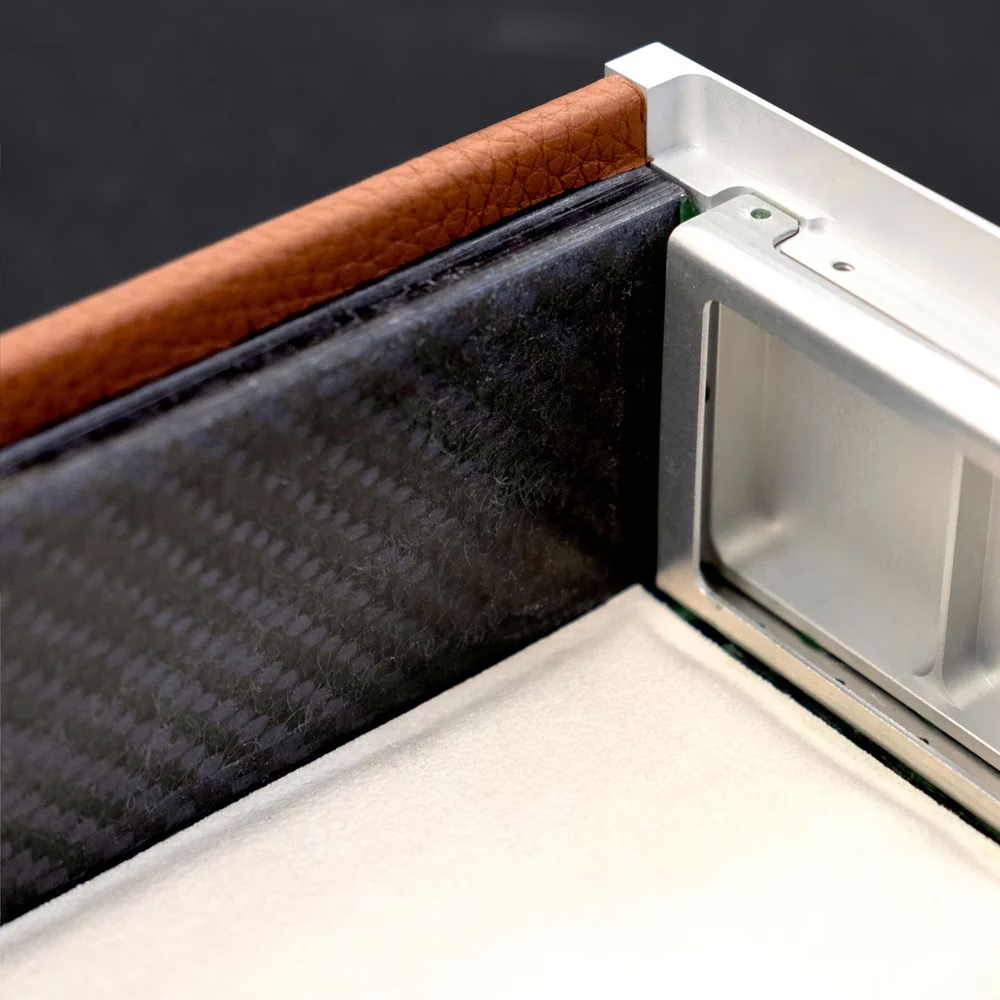

Aerospace-Grade Aluminium

As two ex-aeronautics engineers, it made total sense for Charles and Simon, the founders of the company, to use aluminium for the primary structure of their cases. It’s light, strong and looks beautiful when finished. They design, machine and finish their components themselves to such a high level that they almost look like Patek Philippe movement baseplates. The material, used as the structural frame on products like the Mackenzie Watch Briefcase and the Taylor watch box, adds a touch of modernity to what is an overly traditional part of the industry.

But what is aluminium, and why do some people say its name wrong?

The material was discovered in 1807, but wasn’t widely used until the early 1900. It was so rare that in the 1800s, Napoleon III had aluminium cutlery made for his special guests, where lesser ones had to make do with solid gold. Napoléon le Petit, he was not!

It was mainly used in military aircraft and the manufacturing industry in its early years. Today, it’s one of the most produced metals in the world. As for the incorrect pronunciation, mainly in North America, that comes down to Sir Humphry Davy (the chemist who discovered it). He spelled it Aluminum, even though the rest of the world wanted it to have an ‘ium’ at the end so it better fit in with other elements like sodium, potassium and magnesium. Classic case of stubbornness.

"Aluminum is the engineer's material of choice-light, durable, and endlessly versatile. Using it for our products allows us to deliver design-driven functionality, by creating accessories that are light and sleek enough to feel effortlessly convenient but strong enough to last a lifetime."

C.G.T. Co-founder and CEO of Charles Simon

Rémy Carriat Taurillon Leather

Charles Simon sources their leather from Rémy Carriat, a French tannery founded in 1927. The full-grain Taurillon, or ‘young bull’ leather used, is incredibly supple, but because it includes a textured finish, it’s great for everyday wear and won’t show scratches easily.

When I first held the Mackenzie watch briefcase in my hands, I did what any normal person would do: I held it up to my face and inhaled. Some leathers are so highly processed that they don’t smell like anything, but one sniff of Rémy Carriat’s leather transports you to their workshop in the south of France. This is what I imagine the inside of a vintage Ferrari smells like. The craftspeople at Charles Simon can also inlay the leather in intricate patterns and shapes. It’s incredible work.

"Contemporary craftsmanship requires a process of constant reimagination-letting innovative ideas take shape through a tactile discourse with materials, guided by a deep respect for the trade and a quiet pursuit of excellence."

T. D. L., Leather Expert at Charles Simon

Light Weight Carbon Fibre

What’s interesting about the brand is that some of its most impressive engineering is hidden beneath the surface. Carbon fibre is one of those materials that brings with it a certain prestige, especially in the automotive world. If you’ve ticked the box for an unpainted carbon roof on your 911, for example, it’s a signal to your peers that 1, you mean business and 2, your reduced curb weight and lower centre of gravity mean you could beat them in a lap of the Nürburgring.

In the luxury space, carbon has been used in watches for a while, but it’s always on show, and to me looks a little too ‘technical’. Charles Simon’s use of carbon, in contrast, is purely functional. The internal structures of the briefcases and boxes are carbon fibre panels that reduce weight considerably but don’t sacrifice strength and protection. They could have just used a plastic-based material, and the consumer would generally be none the wiser, but it just feels so good to know what lies beneath the surface.

Canadian Recycled Wood

I’ve been a guitar player for the last ten or so years, and my interest in wood has been described as ‘a problem’ and ‘perverse’ on many occasions. I’m not denying it, I love wood. From rich Brazilian Rose Wood on vintage Martin, to modern companies like Santa Cruz that are using reclaimed ‘Sinker’ Mahogany that is over a thousand years old, there’s a world of wood out there you can’t even imagine. Charles Simon uses Canadian wood for some of their briefcases and boxes (it’s an option), and the story behind it is fascinating.

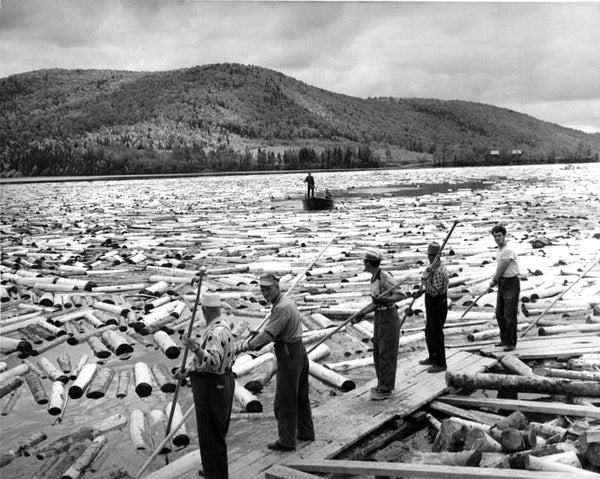

In the middle of the 19th century, river log driving was the main method of transporting cut trees from the forests to the saw mills. The people doing this, ‘draveurs’, were incredible, often jumping from log to log on the long journey down the river. It was a dangerous job, and there were a lot of casualties; it was tragic.

Some of these trees never made it to their destinations, sinking to the bottom of the rivers where they slept for the next 120 years. In this environment, the wood is left to age in a low oxygen environment that produces a rich colour, increased figuring, and unrelated to Charles Simon, more resonance. Sinker Mahogany is prized in the construction of guitar backs and sides because it can vibrate more freely than younger wood.

In cases like the Mackenzie, the team finish the wood by hand and bond it to the aluminium frame directly. On to live another 100 years. It's very special indeed.

The Fifth Element Is Love

Charles Simon is the perfect example of a company that makes products that are greater than the sum of their parts. Although the parts in this case are very, very good, there’s something else baked in that is a little less tangible.

Although I can’t be sure, I feel it’s all the little decisions that were made in the design, the consideration taken in choosing the materials, and the people that put it all together. I don’t want to get all esoteric on you here for the second article in a row (check out my Bovet Recital 12 story), but what makes these products special is their soul.

It’s the soul that the craftspeople embed with their hands, their minds and their hearts.

The unfortunate part about all of this is that their biggest selling point, how their products feel, is almost impossible to convey from a distance. It’s not until you have them in your hands that you truly understand how special the brand is. You need to smell the leather, feel the cold of the aluminium and hear the solid ‘click’ of the latch closing when you press on it.

Just like at the Apple store, Charles Simon products have to be experienced to be believed. It’s just a shame that very few people have the pleasure.

Cya in the next one. X

This story was created in partnership with our good friends at .

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.webp)